Overcoming the False Trade-off in Genomics

Note: This post was originally published for MIT’s Envision the Future of Computing Prize, where it won an honorable mention.

On June 26, 2000, President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair jointly announced to the world that the first draft of the human genome had been completed. Speaking with unfettered optimism on the implications of Human Genome Project (HGP), President Clinton declared:

“Without a doubt, this is the most important, most wondrous map ever produced by humankind. […] It will revolutionize the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of most, if not all, human diseases. […] In fact, it is now conceivable that our children’s children will know the term cancer only as a constellation of stars.”

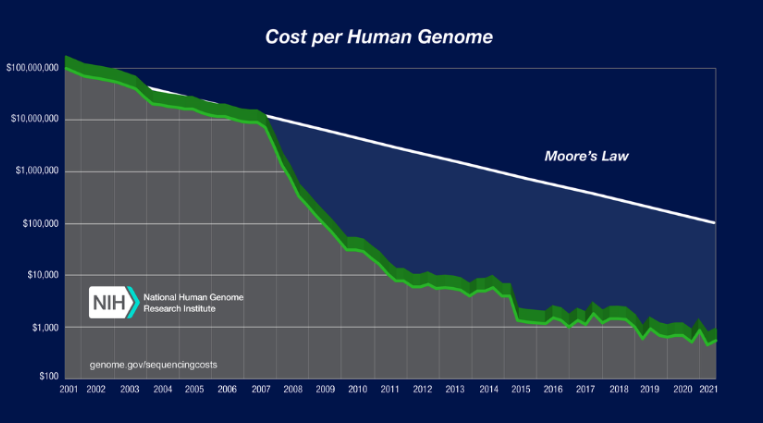

Two decades later, the president’s lofty promises have proven to be somewhat prescient. There is little doubt that whole genome sequencing — now more than five orders of magnitude cheaper than in 2000 — has revolutionized biomedicine.

Pharmacogenomics is already empowering precision medicine targeted to the genetic mutations a patient carries. While a blanket cure for cancer as President Clinton envisioned is yet to be realized, CRISPR gene editing technologies have also generated considerable scientific excitement for the next era of therapeutic medicine. Even long-held anthropological questions regarding human migration can be answered through computational analysis of ancient DNA. These innovations are not limited to academia either. Today, there are numerous publicly traded companies (e.g. 23andMe) whose core products involve sequencing or analysis of genomic data.

Each of these efforts has only been made possible through large international collaborations since the HGP, and further breakthroughs in genomics will inevitably continue to change the pace of drug discovery and biomedical innovation. Indeed, collaboration is at the heart of genomics and biomedical research: groundbreaking discoveries only occur when data is pooled across multiple ethnicities, conditions, and backgrounds.

However, buried within Clinton’s speech were other concerns about the future of genomics:

“As we unlock the secrets of the human genome, we must work simultaneously to ensure that new discoveries never pry open the doors of privacy. And we must guarantee that genetic information cannot be used to stigmatize or discriminate.”

President Clinton’s words were especially important given the historically fraught relationship between population genetics and minority communities. Some of the original titans of the field and inventors of mathematical tools for genetic analysis manipulated their inventions to promote scientific racism. Absent proper safeguards, access to the highest resolution information about human ancestry, DNA, can be used for novel forms of discrimination and surveillance.

As international collaborations explode in size, concerns regarding genomic privacy and ethics are growing; in the past two years, US Congress has debated the federal Genome Data Security Act and California has signed the Genetic Information Privacy Act into law. While these laws aim to protect genomic data, it is unclear exactly what kind of attacks and analyses may be possible in the event of a future privacy breach. As our understanding of the human genome continues to evolve, richer biometric information can be extracted from genomic samples. For instance, prenatal genetic testing can illuminate disease risks prior to birth.

However, we do know two key differences in genomic privacy and ethics concerns compared to other forms of data: (1) unlike credit card numbers or social media, the human genome is immutable, so a one-time leak of information is a lifetime leak, (2) genomes are strongly correlated between relatives, so a leak has privacy implications beyond the individual, for families and even communities.

Traditionally, stronger privacy regulations are considered at odds with collaborative research and development. However, this is simply not an option in genomics, where strong restrictions will prevent life-saving therapeutics from being developed.

In this essay, I argue for the need to develop new technologies that both enhance genomic privacy and foster large international collaborations. Specifically, I argue that the oft-repeated trade-off between privacy and utility is a false dichotomy that can be overcome in genomics with significant engineering and legal effort. We must develop two forms of data security and privacy to enable such collaborations:

- Institutional data security, or security of large-scale biological data repositories, hospitals, and corporations against malicious actors hoping to steal or manipulate this data.

- End-user data privacy, or guarantees to patients participating in studies that their individual data will not be identifiable or inappropriately shared.

Importantly, strictly “legislating” around this privacy issue to institute tighter data access measures will only slow the pace of research and play into the trade-off. Instead, we must lean on new computing technologies to maintain scientific efficiency while promoting security, privacy, and compliance.

A New Era of Collaborative Research

Collaborative scientific research is a prerequisite for genomics. Genetic signatures of diabetes, for example, can differ from population to population, so generalizable and statistically significant findings require pooling data from organizations worldwide. This is reflected in the endlessly growing list of consortia dedicated to the study of biomedical questions through genomics: UK Biobank, NIH All of Us, FinnGen, and so on.

The change is being acknowledged at all levels of biomedical research. President Biden’s cancer moonshot goal — started in his Vice President years — to reduce the rate of cancer deaths by half in twenty-five years includes a project to develop a cloud-based cancer genomic data analysis platform authored by Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, and the National Cancer Institute. Closer to MIT, the Broad Institute is partnering with Microsoft to develop Terra, a secure and efficient cloud-based biomedical data analysis platform.

Researchers, clinicians, and industry partners are using these databases and platforms to improve precision medicine. For example, the Cancer Genome Atlas has gathered more than 2.5 petabytes of data, which has been used to identify key cancer genes like BRCA1 and provide more fine-grained diagnoses beyond the standard stages of cancer.

Kemal Malik, director of innovation for Bayer, highlights the crucial role genomics plays in precision medicine and disease treatment:

“The Holy Grail in health care has long been […] precision medicine. But getting to the level of precision we wanted wasn’t possible until now. What’s changed is our ability to sequence the human genome […] To date, genomics has had the most impact on cancer because we can get tissue, sequence it, and identify the alterations […] In the future we’ll see every cancer patient sequenced, and we’ll develop specific drugs to target their particular genetic alteration.”

Indeed, the key driver of precision medicine has been pharmacogenomics. Under this new clinical paradigm, drugs are prescribed only if the predicted patient response (based on genomic information) is positive. Pharmacogenomics is not a pipe dream: since 2011, the FDA has labeled 250+ prescriptions with dosage recommendations based on genetic differences. For instance, the breast cancer drug PIQRAY was shown to be more effective in patients with a mutation to the PIK3CA gene than those without one. As we develop a more nuanced understanding of pharmacogenomics, it’s possible — even likely — that we will move away from FDA-curated labels to FDA-approved drug recommendation software. Some startups are already testing these waters.

In a related development, CRISPR technologies are moving the needle on gene editing, which could help cure once incurable diseases. After a series of publications in 2012 demonstrating that CRISPR/Cas9 could edit genes through precise cuts and natural repairs to DNA sequences, CRISPR has captured the imagination of biotechnologists worldwide. Vertex Pharmaceuticals has already cured 31 people of sickle cell disease, and other companies are testing preclinical drugs. Scientists have also been using CRISPR to develop tests for infectious diseases at lower costs than PCR tests and even extreme-weather resistant crops.

Genomics has even answered questions in social sciences. Geneticists like Svante Pääbo (2022 Nobel Laureate) have leveraged computational techniques to unlock age-old questions about human migration. By mapping and comparing fragments of DNA found in ancient human bones, they have been able to establish new lineages in the human story, like the archaic humans from the Denisovan caves, whose genomes account for up to 5% of some modern lineages.

Characterization of Privacy Risks

In parallel with the scientific advances, the call for genomic privacy has grown from a mellow hum to a thunderous roar. It is natural to believe that the path forward for genomics is to remove barriers to collaboration, a route which has already provided numerous discoveries. However, without proper safeguards, the rift of trust between the public and medical science will expand. One can only imagine if baseless conspiracies — such as claims that COVID vaccines directly edit human DNA — are provided genuine substance in the event of a large-scale genetic privacy breach. Maintaining trust is one of many concerns, and as we expand these collaborations public trust must be paramount.

Early privacy studies indicated that relatively few — just 75 — genomic coordinates (“single nucleotide polymorphisms”) were needed to uniquely identify many individuals, but it was unclear how such findings would generalize given the sparsity of large-scale sequencing databases. Re-identifying individual genomes at scale seemed akin to searching for a genetic needle in a haystack of DNA.

At some point in the 2010s, the tone shifted. A flurry of papers demonstrating that anonymized genomic data could be linked to individuals or other phenotypic information raised alarm. One landmark study in 2018 leveraged paternal surname inheritance to link anonymous genomes to specific names. By exploiting the Y chromosome — present only in males and thus, like surnames, typically inherited from the father — and a small (private) database of labeled genomes, researchers were able to triangulate the identity of a substantial fraction of males. Extrapolating from their results, they estimated that 12% of all European descent males in the US were susceptible to such an attack. Responding to the work, Eric Green, former director of the NIH Human Genome Research Institute, noted, “we are […] an awareness moment.”

Since the publication of this and similar attacks, new avenues of privacy breaches have been demonstrated, both in real-world and sandboxed settings. The attacks run the gamut of techniques, but some noteworthy examples include:

-

Reconstruction of private genomes by repeatedly sending (legal) queries to a server.

-

A data breach from servers of a company due to unencrypted data stored on a problematic server.

Unlike other forms of data, genomic data is immutable, so these attacks have implications well beyond the victim and the specific time of the attack. It is nearly impossible to think of another type of data which, if leaked, can reveal sensitive health information of the victim’s future great-grandchildren. Brad Malin, professor of computer science at Vanderbilt, notes that the risks are “highly dependent on how the adversary wants to use the data.” Feasible possibilities include employment and housing discrimination based on genetics, which is legal in certain municipalities at the moment.

In response, various government agencies have begun instituting tighter controls for genomic data. Last year, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) announced a new project to “identify genomic data cybersecurity and privacy concerns and develop guidance to address these challenges.” NIST’s project touches all levels of genomic analysis, from ensuring that sequencing devices themselves are secure to writing better access protocols for genomic data repositories.

FBI agent Ed You notes that “cross-border deals are not the only risks to US genetic data. The healthcare industry is notoriously vulnerable to cyberattacks.” These concerns have directly influenced legislation. Four states have passed genetic privacy protections, and Congress is currently considering the Genomic Data Security Act, a bill which would place restrictions on Chinese access to American genomic data.

Overcoming the Privacy-Utility Trade-off

A False Trade-off?

Typically, the tension between privacy and collaboration is framed as zero-sum. Former UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock bluntly noted that: “it’s outrageous that too often, anonymised data […] can’t be used for research. We will unlock that data because […] it saves lives.” Hancock’s concerns are reasonable and highlight the cost of strict measures: patient lives. Nonetheless, the false dichotomy is dangerous and could lead us into a vicious cycle of removing access barriers only to later realize privacy issues. We must therefore overcome Hancock’s implicit belief that privacy and collaborative research are “too often” at odds.

The previous attacks demonstrate a need for both institutional data security and end-user genomic privacy paradigmsto overcome this double bind. While the distinction is somewhat artificial, attacks stemming from unauthorized access fall more in an institutional oversight realm. On the other hand, reconstruction of a private genome through public queries seems to be an end-user privacy issue.

The distinction is perhaps best explained by the services offered in the financial sector. If a bank liquidates, it is typically blamed for its poor institutional management. To compensate for this, end users can choose to only hold savings in FDIC-insured banks, so that their money is federally insured in case of mismanagement.

Despite strict privacy regulations, a thriving market — fintech — exists to provide customers with better solutions and overcome a double bind. A similar balance is needed in genomics.

A Response from Computing

Several computing technologies actively being developed at MIT could empower the secure and efficient genomic data collaboration needed to overcome the false trade-off between privacy and collaboration.

On the institutional data security front, there are proof-of-concept and real-world applications of cryptographic tools to enable secure collaboration. As an instructive example, imagine there are three biobanks which would like to jointly analyze their data without revealing their private patient data.

Secure multiparty computation (SMC) defines a set of protocols which enable joint computation of a function when the data is distributed across multiple parties. For example, if the function to compute is $F(x,y,z) = xyz$, then SMC allows the parties which separately own $x$, $y$, and $z$ to compute $F$ without revealing anything about their inputs. The key method behind SMC is known as secret sharing, which uses some elegant properties of polynomial interpolation to guarantee security.

This is a promising paradigm for collaboration, as functions we would like to compute over distributed datasets could now be computed in cryptographically secure ways. Researchers at MIT have already shown proof-of-concept results for collaborative genomic analyses — such as gene-disease studies — using SMC without sharing raw patient data.

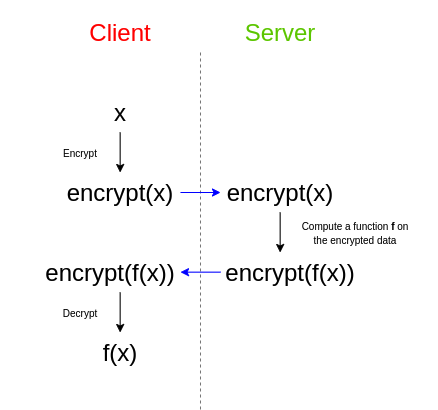

In a separate but similar setting, imagine a hospital holds a partial genomic sequence of a patient and would like to impute the rest. Genotype imputation is an expensive task, so the hospital asks a remote server to help with the imputation. Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) allows direct computation on encrypted data. In this paradigm, the hospital sends an encrypted genome to a remote server, which provides (an encrypted version of) the correct answer without learning the input.

While FHE/SMC provide cryptographic security guarantees, engineering them to be efficient is challenging in practice. The additional memory requirements for these technologies makes computation exceedingly burdensome in many cases, and each line of the computer program further elongates the runtime. Limited network bandwidths can explode the total time required if the network traffic needed for the protocol is high. For these reasons, SMC/FHE are yet not used at scale in practice. These protocols are especially hard to implement for intrinsically resource-intensive computations like deep learning. We therefore must continue developing and deploying scalable SMC/FHE and related technologies to provide a bridge — cryptographically secure protocols for widespread collaboration — across the false trade-off between privacy and collaboration.

On the end-user data front, methods like differential privacy are providing stronger guarantees that individual patient data will not be leaked through some of the statistical attacks described earlier. Differential privacy — a technique that adds noise to any aggregated data releases — provides a mathematical framework to pinpoint the chance that a patient’s data can be re-identified from legal queries to database. Calibrating the correct noise to add is notoriously difficult: too little noise weakens privacy while too much noise can muddle important downstream analyses.

The solution in applications thus far has been a tenuous consensus from experts and stakeholders. Even with such careful deliberations, institutions like the US Census have received criticism for their noise levels.

It is unlikely that any noise level — or any cryptographic protocol — will satisfy everyone’s preferred privacy level. Privacy is inherently personal: you may mind your friend snooping through your text messages, but your neighbor may not. The only truly trustworthy and long-term solution is to therefore offer fine-grained consent laws to users. These laws should enable users to specify who to share their data with and what analyses are allowed with their data. At the loosest level, no protections will be available beyond what is federally required. At the strongest level, the user can retract their data from a database and scrap any traces of it anywhere. An in-between level may include an authorization for use in collaborative studies, but only if technologies such as FHE/SMC are used.

The specific formulations of consent will require the collaboration of patients, clinicians, researchers, and legislators, but the need for fine-grained privacy laws is clear.

A Look to the Future

Perhaps President Clinton will prove to be right, only several decades later. It is conceivable that certain rare diseases and cancers will only be historical afflictions at some point in the 21st century. As ambitious as that may seem, the 20th century brought miracle cures: a polio vaccine, the first antibiotics, and IVF babies. Unlocking the human genome will provide many more.

As we look to this future with starry-eyed optimism, it is critical that we not get locked into an endless debate between privacy and utility. Instead, we must imagine new worlds — both technologically and through legislation — in which the two co-exist. Bridging the gap between privacy and collaboration is the only way forward to save as many lives as possible, and some of the ideas introduced here could lead the way. It is only through locking our genetic secrets that we can fully unlock our genome’s revolutionary potential.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: