On Voting Paradoxes

Note: This post was originally published on my old blog.

My post last week sent me down a Wikipedia/Google rabbit hole on voting systems and paradoxes. I’d heard in passing about voting paradoxes but never took some time to explore them. In this post, I’ll discuss how we can use graphs to model elections and then explore the ideas behind voting paradoxes.

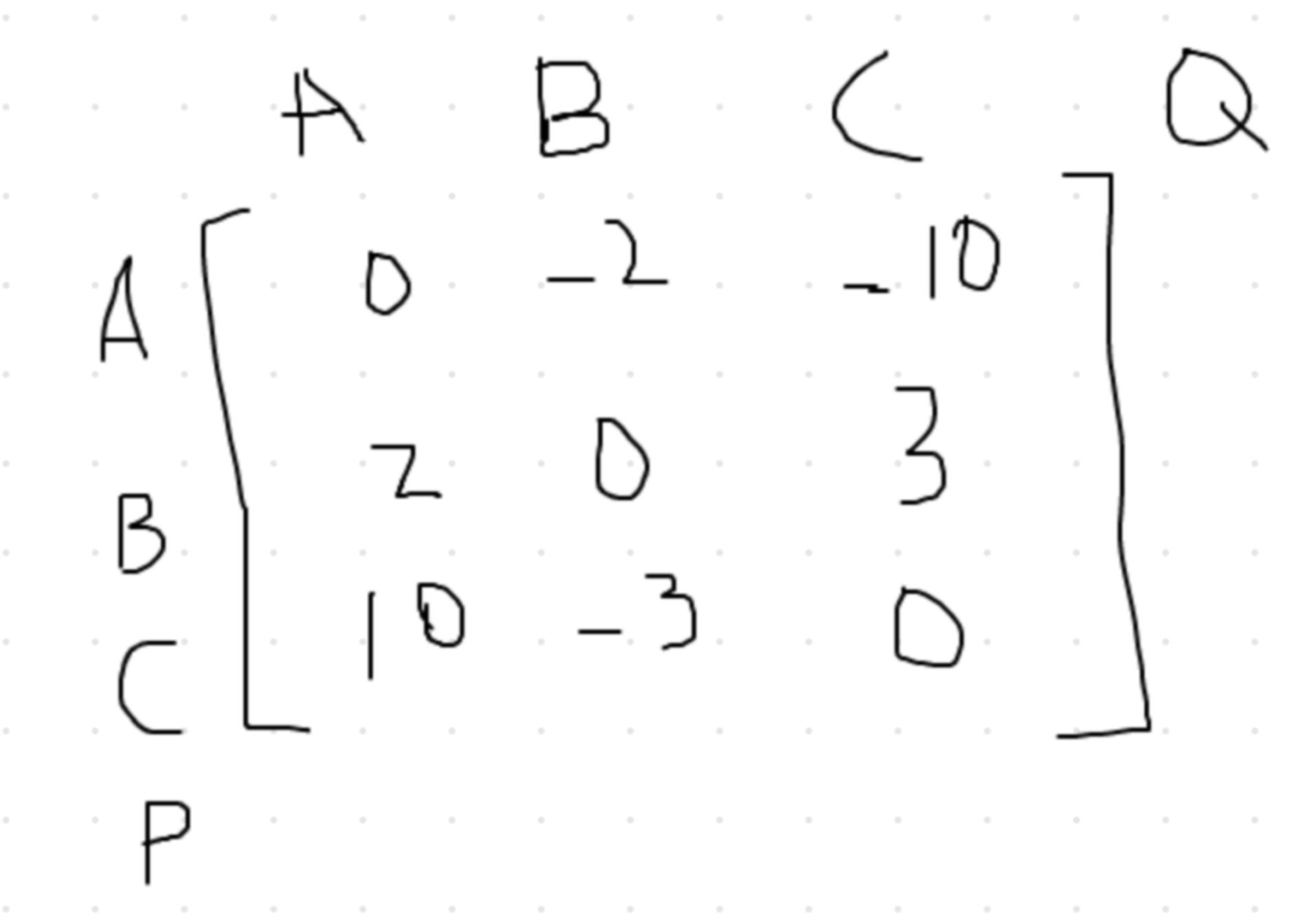

I. A Graph Reduction for Elections

To start, let’s define some notation (note: a lot of the ideas here are from this paper, so check it out if you’re interested!). Suppose we have $m$ candidates, who we’ll call $c_1, \ldots, c_m$, and $n$ voters, with each voter casting a ballot ranking some or all of the candidates. Each ballot is an ordered set $B_i = {c_{(1)}, \ldots , c_{(m)}}$ corresponding to the voter’s preferences. We can then construct a collection $C$ of ballots ${B_1, \ldots, B_n}$ of everyone’s votes, which we’ll call the election profile. Our goal is to determine a “fair” method to select a winning candidate. If we choose to represent the election in matrix form, then let $M_{i,j} = \sum_{B_k \in C} I(B_k \text{ ranks i over j}) - I(B_k \text{ ranks j over i})$ (intuitively, it’s just the margin of voters who prefer $i$ to $j$). Note that this matrix is antisymmetric ($M^T = -M$) with a zero diagonal.

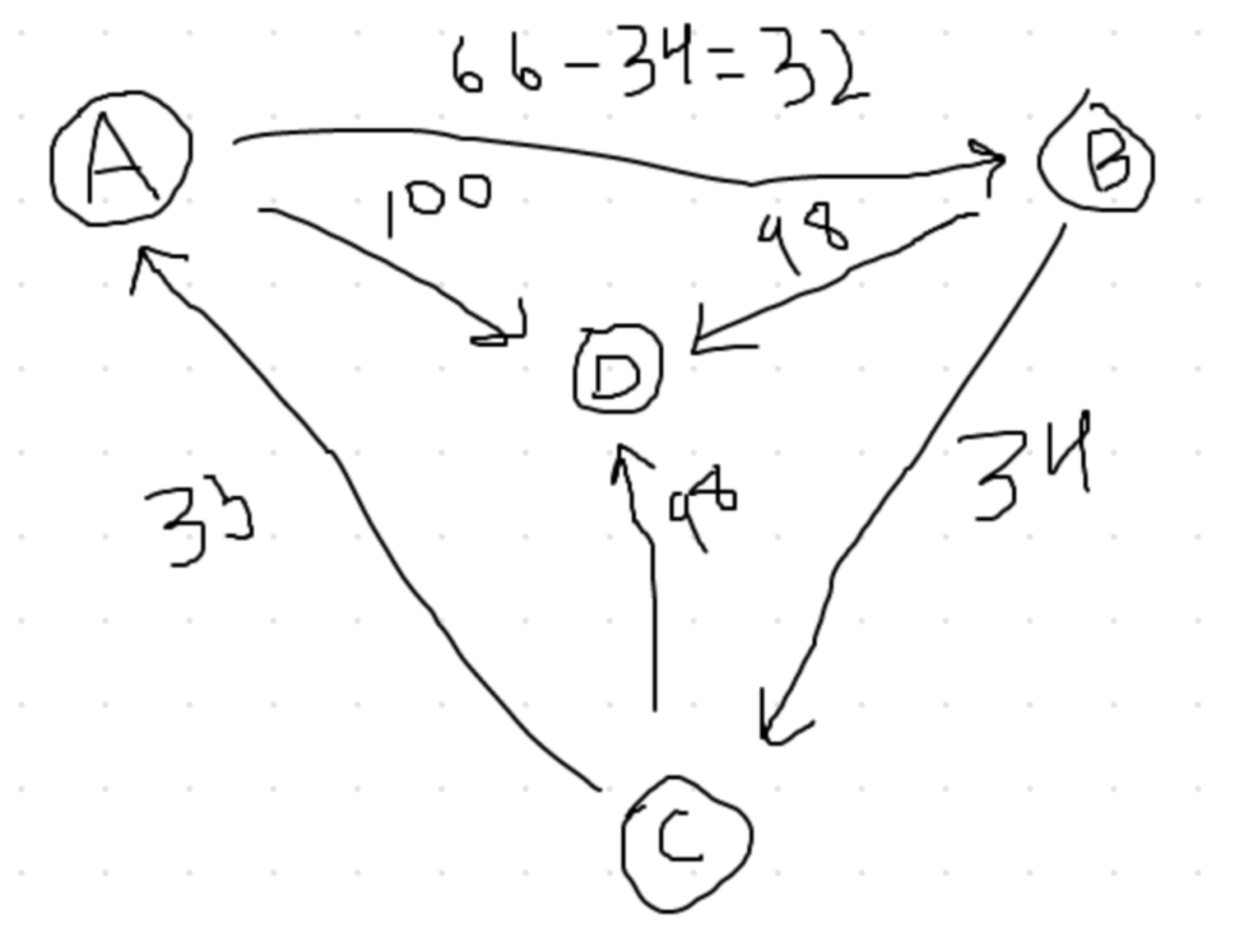

However, we can model this election as a graph, with vertices corresponding to candidates and directed edges corresponding to the margin of votes between any pair of candidates. In particular, if there are $m$ total voters and $k$ ballots rank candidate $A$ over $B$ (so $m-k$ rank $B$ over $A$, for simplicity) with $k > m-k$, then there is an edge from $A$ to $B$ with weight $k – (m-k)$. Conversely, if $m-k > k$, then there is an edge from $B$ to $A$ with weight $m-k-k$ (and if $m-k = k$, no edge exists).

(Feel free to skip this section if you’re comfortable so far) To see the graph and matrix representations of the problem more concretely, let’s imagine an election with four candidates, {A, B, C, D}, and 100 voters. The ballots break down as follows:

| Voters | Pref. 1 | Pref. 2 | Pref. 3 | Pref. 4 | Ballot ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | A | B | C | D | 1 |

| 34 | B | C | A | D | 2 |

| 32 | C | A | B | D | 3 |

| 1 | A | D | B | C | 4 |

To determine the edge weight and direction between $B$ and $D$, for example, note that 99 ballots prefer $B$ to $D$ and 1 prefers $D$ to $B$, so we will have an edge from $B$ to $D$ with weight $99-1=98$ in our graph. In our matrix, $M_{B,D} = 98 = -M_{D,B}$. The graph representation is shown in Figure 1.

There are some paradoxical results here: if we choose $A$ as the winner, note that ballots of type 1 and 3 both prefer $C$ to $A$, of which there are 65 total voters, so a majority prefer $C$ to $A$. However, 67 voters prefer $B$ to $C$, and 66 voters prefer $A$ to $B$, yielding a paradox. We could break this tie by counting who is most preferred over $D$, but that would make the last ballot a “dictator” ballot (in that one person’s vote is used to break a tie in favor of $A$, even though $C$ is preferred to $A$).

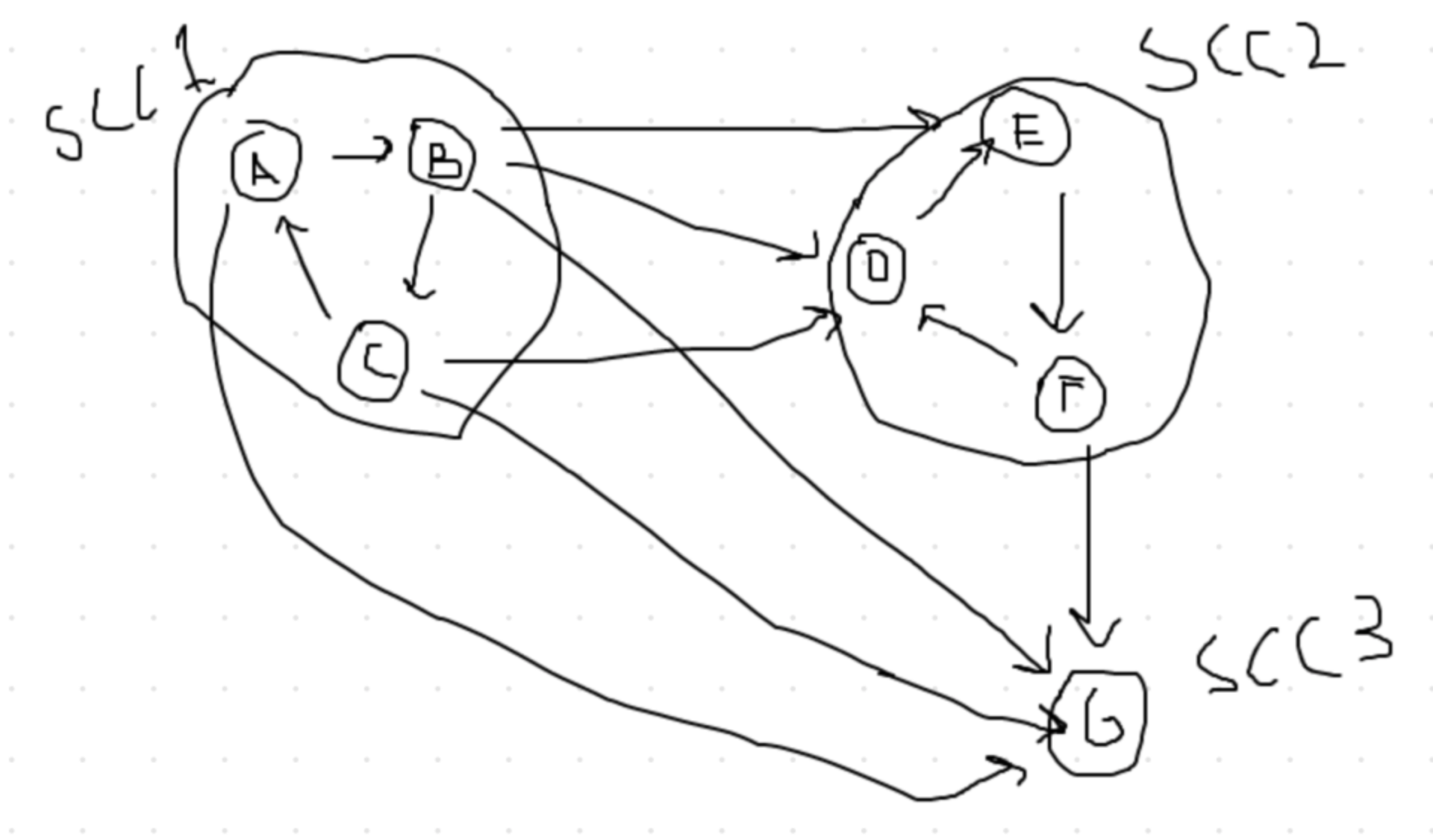

This reduction (/framework) can actually provide some good intuition on elections, as we can translate graph problems and their corresponding algorithms to voting systems, and vice versa. For example, suppose we wish to determine the smallest set of candidates, $S$ such that every candidate in $S$ would beat every candidate not in $S$ in a head-to-head matchup (economists call this set the Smith Set). Equivalently, we have a directed graph over all the candidates, and we wish to find the smallest set of vertices such that there are no incoming edges and there exists at least one path to every vertex outside of $S$. But this set is just a source strongly connected component: we have a set of vertices with a cycle amongst them, but there are no incoming edges.

Tarjan’s algorithm can find us a source SCC in linear time, and we can check whether every vertex outside the set is reachable from every vertex in the set (equivalently, whether every other candidate outside the Smith Set is beatable) by running a Depth First Search (DFS) from one of the vertices in the source SCC (to prove this, start by noting that an edge exists between any two candidates except in the case of a tie, and use SCC properties from there). Figure 2 shows an example. In fact, any graph ordering algorithm, such as topological sorting, can be interpreted as a method for ordering candidates in some way (for every pair of candidates $A, B$ with $A$ before $B$ in the topological sort, $A$ must not lose to $B$).

In practice, finding the Smith Set can be used to winnow down a large pool of candidates to a smaller pool for a “runoff” election such that every candidate in the runoff would beat every candidate not in the runoff in a head-to-head election.

It turns out that any deterministic method to select a winner (either by assigning weights to votes, or using some other method) can be broken with some paradoxical election. The paper I linked earlier proposes a randomized solution, which I discuss in the second half of the post.

II. A Randomized Solution for Paradoxes

To evaluate voting systems, we need some method for comparing two systems (i.e. some notion of voting system $X$, like first past the post, being better than voting system $Y$, like ranked-choice). First, a voting system is merely a function which takes an election profile $C$ of all ballots cast as input and outputs a single winning candidate. The exact profile, $C$, is one drawn from a distribution $D_C$, assigning probabilities to specific election profiles (this is natural; we tend to think of our own elections as having some level of noise). That is, each possible election profile has an associated probability. If there were three candidates and 10 voters, our distribution could assign a probability of 0.1 to (a profile of) 9 voters selecting {A, B, C} and 1 voter selecting {C, B, A}, for example. Every possible profile would have an assigned probability, which would give our distribution of election profiles.

Let $P$ and $Q$ be specific voting systems, with $P(C) = x$, $Q(C) = y$. That is, on a given profile $C$, $P$ chooses $x$ as the winner, and $Q$ chooses $y$. The relative advantage of a voting system is just:

\[\text{Adv}_{D_C}(P,Q) = E_{D_C} (M_{x,y} / |C|)\]It’s important to keep track of what’s fixed and what’s random here. The quantity inside expectation says: “given a particular profile $C$, what is the margin by which voters prefer P’s winner to Q’s winner, normalized by the total number of ballots.” If $P$ selects a winner less preferred than $Q$, then $M(x,y) < 0$, and vice versa. We wish to calculate this quantity over all profiles, and thus take an expectation with respect to the distribution of profiles. More simply, P and Q give winners $x$ and $y$ for a particular profile $C$. We can calculate a “margin” $M(x,y)$ giving the number of voters who prefer $x$ to $y$, as well as the probability that $C$ is the actual profile. We now have two quantities: a margin and an associated probability, so we can take the expected margin between voting systems $P$ and $Q$. Intuitively, the relative advantage represents how many voters prefer $P$’s winner to $Q$’s winner in an average election.

Then, $P$ is as good as or better than $Q$ if $\text{Adv}{D_C}(P,Q) \geq 0$, and $P$ is optimal iff for every other voting system $Q$, $\text{Adv}{D_C}(P,Q) \geq 0$.

Given this method for comparing voting systems, we can now try to construct the optimal voting system. To do so, we’ll borrow some ideas from game theory. In particular, let the margin matrix $M_{x,y}$ be a payoff matrix and let voting systems $P$ and $Q$ be players in a two player game on this matrix. So, if $P$ selects $x$ as the winner and $Q$ selects $y$, $Q$ “pays” $M(x,y)$ to $P$. An optimal voting system $P_{OPT}$ would have non-negative expectation no matter what strategy is used by a competing voting system. The expected payoff of a voting system $Q$ to $P$ is:

\[\sum_{x,y} p_x q_y M(x,y)\]If $Q$ is a deterministic voting system (i.e. $q_y = 1$ for one candidate, $0$ for all others), then $P$ can always just select the candidate which maximizes this payoff, and always do at least as well as $Q$ (i.e. never have more voters prefer $y$ over $x$ — in the worst case, $P$ and $Q$ just choose the same candidate).

But $M$ is anti-symmetric, so the column player and row player (or $P$ and $Q$) are interchangeable. The optimal strategy is a mixed strategy, in which $P$ assigns each candidate a probability of being chosen as the winner and selects a winner according to these probabilities (for two player games, this equilibrium is the Nash equilibrium). This optimal mixed strategy can be calculated using linear programming, and no mixed strategy can beat this strategy in expectation (follows from minimax).

That was a lot, and if you want a better explanation, I’d encourage you to look at the paper, which goes into much more depth than I do here. They also write a number of simulations comparing the randomized system to other voting systems for various election profile distributions. The basic idea, though, is simple: no voting system can beat a randomized voting system in expectation.

There are some interesting extensions of this study worth exploring, such as how the optimal strategy changes for different distributions of election profiles (in reality, we probably wouldn’t expect a uniform distribution over profiles), under what constraints a deterministic solution is best, and the characteristics of bad voting systems — i.e. which voting systems most often lose to random?

It feels as though there’s something inherently undemocratic here, as democracy shouldn’t leave election winners to chance. I’d agree, and I think there are practical benefits to a well-designed, (possibly) paradoxical/unfair system that everyone understands and trusts. Maybe that system is a two-party system, maybe it’s ranked-choice as I discussed in the last post, or maybe it’s something else, but this framework for understanding voting can help guide our decisions.

That being said, I think it’d be interesting to implement a randomized voting systems in certain circles (such as selecting leaders of scientific communities?) as test runs.

III. Addendum (2025)

I ended up simulating the randomized voting system above (with my classmate Sahana Srinivasan), using both some toy distributions and some real-world(!) election profiles from American cities in a class project for Ariel Procaccia’s CS 238 class, which I highly recommend. If you’re really interested, you can attempt to scour our code.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: