Democracy and the Central Limit Theorem

Note: This post was originally published on my old blog.

In the spirit of trying to reframe legal and philosophical questions through statistics and computer science frameworks, I thought I’d write about some parallels I see between democracy (or lack thereof) and probability. The law of large numbers and central limit theorem are ubiquitous, so it should be no surprise that we leverage it in so many algorithms and applications (like variational inference, maximum likelihood, etc.). At its core, democracy is an application of the central limit theorem: averaging together the many (possibly extreme) preferences of people guarantees some “average” preference which is perhaps not optimal, but certainly not terrible.

Democracy is an average of preferences, but, in keeping with the previous post, let’s consider it an average of ethical frameworks as well (people’s preferences are guided by their ethical views, so this is a reasonable assumption).

Suppose we had some method for scoring people’s “goodness” and “badness.” You and I may have different notions of what it means to be good, but our scores will almost certainly be correlated; we both think, hopefully, that it’s bad to murder and good to be kind to others. For the sake of this post, let’s stick to one scoring method, which we’ll call $S$ (every person $i$ may have their own method $S_i$, but the expected correlation between scoring methods is quite high).

Let’s now define a distribution $D_S$ of people over these scores. That is, given a random person in the world, what’s the probability that they are at least as good as some score $x$? This will just be $P(p_i \geq x) = 1 - F_{D_S}(x)$.

Note that with one random draw from this distribution, we are more likely to get extreme values, but, as the Central Limit Theorem tells us, as we draw more and more samples, the average will converge to the distribution’s true average (and the variance will asymptote towards zero).

This provides us with a basis for understanding democracy; we average the (possibly extreme) preferences of many, many people with:

- The assumption that extreme preferences are more likely to be worse for society than average preferences.

- A belief that the average human being is good.

I’d argue that these are two reasonable assumptions. First, note that one bad apple can spoil the lot. That is, it only takes one person with extreme preferences to ruin the lives of thousands of people with average preferences. A great example of this would be North Korea, where Kim Jong-Un single handedly has the power to enact any law he’d like (and unfortunately exercises this power often). In everyday life, mass shootings carried out by one person can ruin the lives of hundreds. More mathematically, suppose 1 out of every 100 people is a psychopath and scores extremely low on some goodness rating (so probability that some random person is worse than this person is 1%!).

Dictatorships, which are analogous to one random draw from $D_S$, would give a 1% chance of selecting someone this bad, and that’s not even considering the lack of accountability that may further corrupt the person’s morals! Democracies, on the other hand, would almost surely prevent this possibility. So, in any functional society, it’s necessary to protect the masses against the tendencies of an extreme few.

Why, then, do democracies fail to elect good leaders sometimes? A few theories may help explain:

-

CLT only holds under IID assumptions. That is, each voter must be drawn from the same distribution. This distribution is not static; it can be influenced by media, family, friends, etc., but on the day of the election, each voter is an IID draw from the distribution. In reality, this is sometimes not the case. Voter suppression (such as not letting certain minorities vote), election rigging, and misinformation can skew this distribution and/or violate the independence assumption.

-

Suppressing others’ votes is probably correlated to psychopathic tendencies (or scoring “bad” on the scale), so the “bad” people are oversampled relative to the “good” people.

It’s no surprise that these ideas are not new; in fact this paper by two philosophers explores applications of Condorcet’s Jury Theorem. The theorem is simple and follows from basic probability (some binomial sums):

“Suppose voters have to decide between one incorrect and one correct option (imagine a jury, where there is a true verdict). If p, the probability of voting correctly, is greater than ½, then in the limit, the probability that the voters choose the correct decision is 1. If p is less than ½, then in the limit, the probability that they vote correctly is 0.”

There are some interesting consequences of this theorem. For example, with 100 million voters and a 50.1 percent chance of a voter voting correctly (suppose “yes” for proposition A), there’s practically no measurable difference (i.e. p-value « 0.01) between 51% of voters choosing proposition A and 70% of voters choosing A. This seems particularly bizarre, because we traditionally think that a larger vote share gives the winning candidate a stronger mandate. If we think a 70-30 margin is a landslide, then what’s to say a 51-49 margin is not? After all, in elections, one could argue that our null hypothesis is the two candidates being equally popular and that the election is testing that hypothesis (what’s the point of an election if the null is that one candidate is preferred?).

The upshot of all this is that in order for democracies to work, we need voting systems in which each individual vote actually reflects the voter’s preferences. Right now, we assume that a Bernoulli draw for each voter between two candidates (probability $p$ of choosing A; $n$ independent draws) is the correct model, but there are probably better systems out there. We’re forcing people to approximate their ethical frameworks and policy preferences on a ${0,1}$ support!

One possibility could be a ranked-choice voting model, which would expand the support of the distribution. That is, if we have, say, 5 candidates, with 5 points to first choice, 4 points to second choice, and so on, we’d have a much larger support (120 possible orderings of the candidates). Each voter could then choose to align their preferences from one of 120 possible scores, which would enable us to capture more information about preferences from each vote. See the diagrams in the appendix for a more rigorous explanation.

Appendix

Diagram for Ranked Choice Voting

I’ve included a couple diagrams below to clarify how ranked choice voting better approximates the average preferences. Suppose for simplicity that there are only two axes, healthcare and economy, along which everyone aligns (say more positive is more privatization, more negative is more centralization).

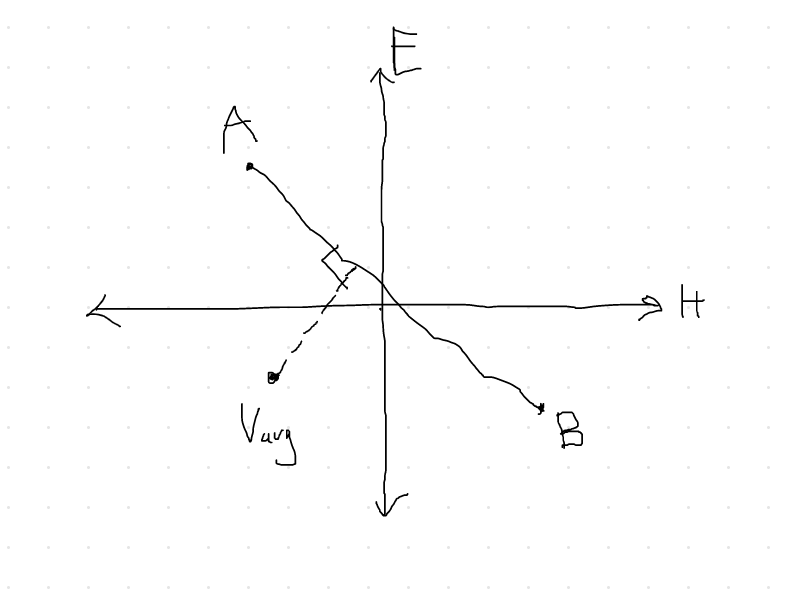

Note that in forcing voters to choose between two candidates, we constrain the national vote to a line drawn between these two candidates (see Figure 1). The election therefore becomes a projection of the true national preference, $V_\text{avg}$, onto this line between candidates A and B.

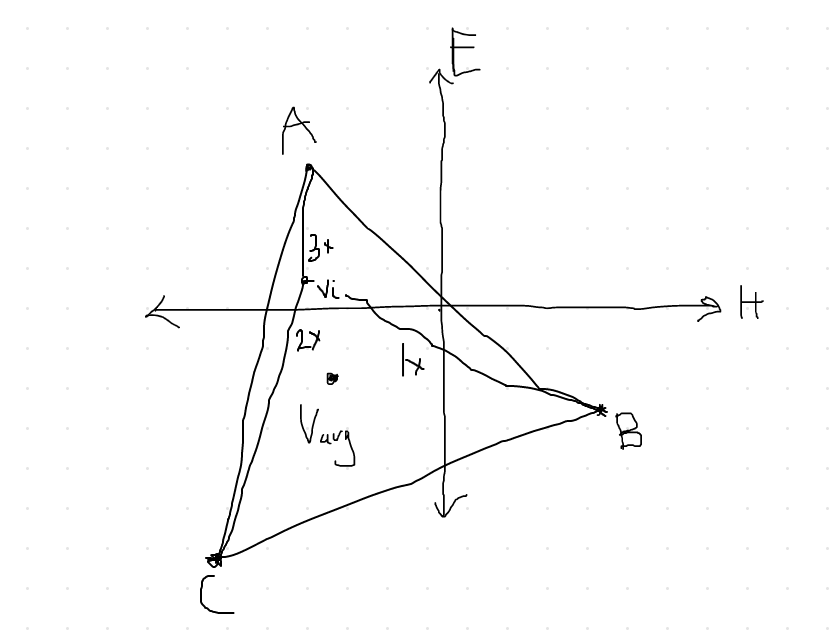

With ranked choice voting and more candidates (suppose three, in Figure 2), each vote can be a weighted sum of all these candidates’ positions on healthcare and economy, so the space of possible solutions (or final vote tallies) is less constrained. The national vote is then constrained to a triangle defined by these three points, and the election is a projection of $V_\text{avg}$ onto this triangle. Each voter $V_i$’s vote is a weighted average of the three candidates, and the election is an average of all $V_i$.

Discussion of Dictator Model

Here we made the assumption that dictators are akin to one random draw from the national distribution of preferences, but relaxing this assumption actually yields even worse results for dictatorships. There’s some negative selection here; dictators are more likely to have narcissistic and psychopathic tendencies to reach the positions they reached, so sampling a dictator from a population is probably even more skewed to the undesirable portions of the distribution.

Other Assumptions

Several people have pointed out that if the average voter has “bad” preferences, democracies will also fail. This is certainly true, and I thought about including it, but the focus of this article was a theoretical justification for democracy assuming the average voter has “good” preferences. To me, these are two separate (but both very important!) questions, as democracy hinges on two assumptions: (1) voters are “good” and (2) given that voters are “good,” the voting system approximates their preferences well.

There are a variety of problems that can complicate the assumptions in (1), including, but not limited to, the average voter being “bad,” herd mentality, tyranny of the majority, and misinformation.

There are also some issues with the ranked choice model’s feasibility in the United States, given the existing two-party structure (and all sorts of other issues). Again, this is not an endorsement for ranked choice voting’s implementation but rather a (more) mathematical exploration of the differences between voting systems.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: