A Statistical Analogy for Ethics

Note: This post was originally published on my old blog.

I’ve grown a little frustrated in how morality and moral law are often misused in public debate.

To start, let’s consider what a moral framework entails. In some sense, moral philosophy is merely a model to determine whether an action is right or wrong. Different frameworks specify exact models for understanding right and wrong; some consider the output a spectrum; others consider it a binary; others even say it’s impossible to interpret any output.

It’s important to note that the model itself is distinct from the political legitimacy of the model (i.e. how well a model is accepted as legitimate by the government). Our federal laws, for example, realize a philosophical model with strong political legitimacy, but federal laws are amended and changed when that model does not coincide with some other, “truer” philosophical framework.

This notion may seem excruciatingly obvious, but you’ll frequently hear accusations of setting “arbitrary moral guidelines” or appeals to the constitution because it was “willed by the people.” These attacks only undermine the political legitimacy of the chosen moral framework, not the internal validity.

It’s equally frustrating when critics of a certain moral framework find tiny, irrelevant exceptions as conclusive disproofs. Just as we wouldn’t discard a machine learning model because of occasional errors, we shouldn’t discard philosophical frameworks because we can find exceptions to them.

Instead, a more convincing critique takes issue with the assumptions made by the model, similar to how we’d criticize a poorly applied machine learning method.

Moreover, any philosophical framework necessarily makes simplifying assumptions and prescribes categorical laws. Utilitarians may shake their fists at me and argue that utilitarianism maximizes good, but I would argue that any framework attempts to maximize good, so this naive utilitarianism fails to prescribe action. Without an exact set of ascribed utilities to actions, I cannot guide my action to “maximize good.” And once you give me this set of weights, it’s almost certainly possible to find a counterexample.

Reaching moral skepticism from these observations is even more preposterous: that would be equivalent to saying “because physics is sometimes contradictory, we should discard our entire conception of the universe.”

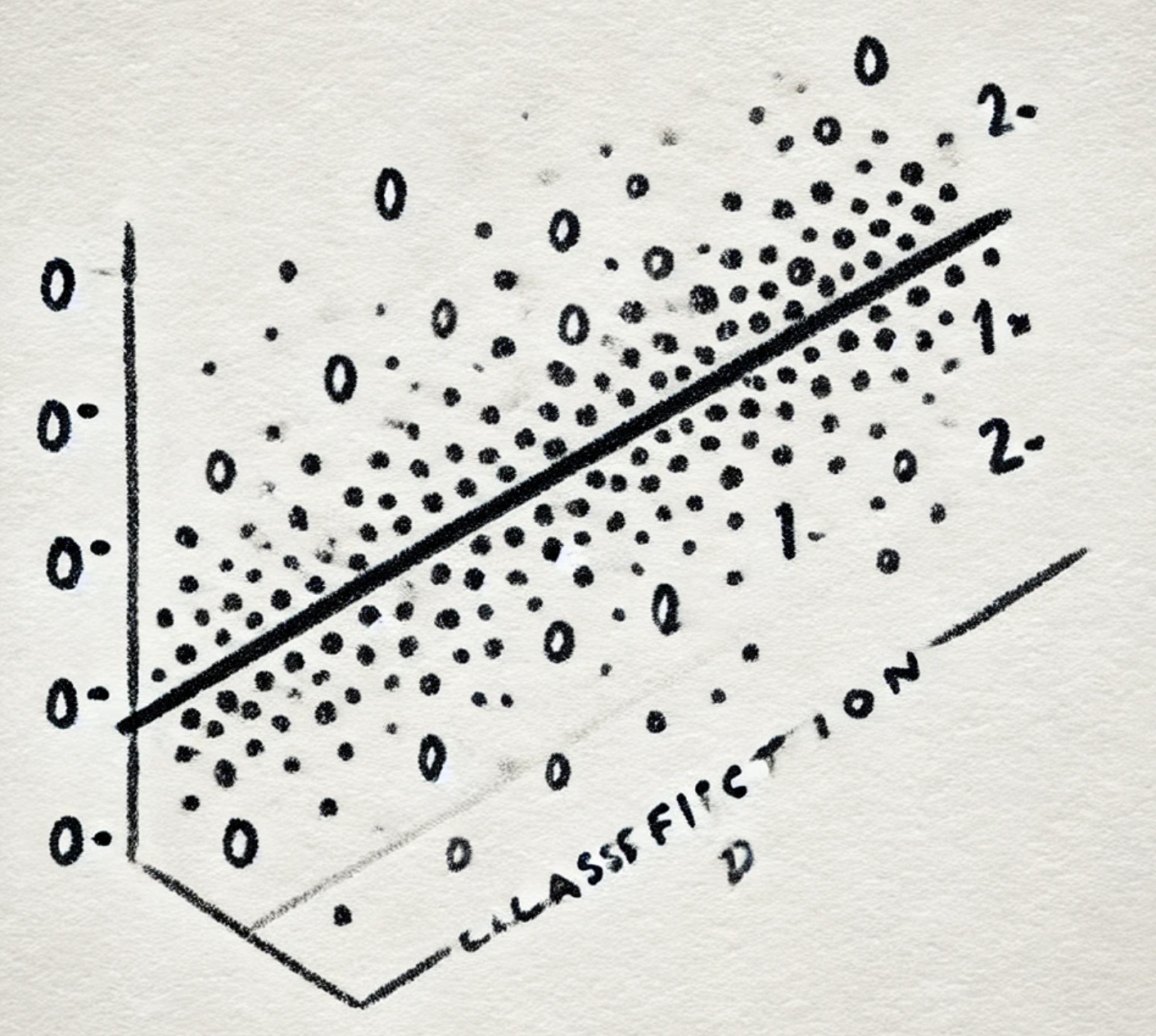

To see how all of these pieces fit together, let’s imagine morality as a sort of mathematical problem. Imagine we have a set of (many, many) axes which contextualize each action we take (e.g. the time of the action, who is there, their positions in society, etc.—every possible degree-of-freedom of a given action). Each action we take is a dot in this large grid, and we wish to classify these dots as moral (“1”) or immoral (“0”) decisions (or a regression problem if you believe morality is a spectrum). There exists a true classification (although this is debatable), and we want to find a model that best approximates this true classification.

We can, therefore, think of categorical laws such as “never steal” as analogous to simpler models like linear regression. We can add conditions to increase model complexity, such as “never steal unless the person is six feet tall and has seven kids.” More generally, model complexity, bias, and variance in machine learning can be analogized to moral frameworks:

-

Model Complexity: As we increase model complexity, we lose interpretability, which is especially concerning in moral philosophy (which serve as interpretable guides to action), so we should penalize convoluted moral frameworks.

-

Interpretability Taken to an extreme, we can have vague and uninterpretable moral models, which, while perhaps technically “correct,” could be very “noisy” and uninterpretable, paralyzing action. Many formulations of utilitarianism fall under this umbrella, in which someone blindly asserts that the best thing to do is to do the most good and then quantifies some metric like maximizing total happiness. Absent a concrete method to achieve this ideal, utilitarianism can be used to justify almost any policy with some set of weights. Think about it: when is the last time a politician made an argument and didn’t invoke some form of “everyone will be better off?” Instead, if we trade some model complexity for categorical laws (which international law aims to do, for example), we may often achieve better results, even by the utilitarian’s own metrics, similar to how we often aim to achieve the optimal “tradeoff” between bias and variance in selecting machine learning models. Perhaps going down this path may lead one to rule utilitarianism.

-

Bias and Variance: While simple moral models may have high bias (i.e. inaccurate in many scenarios), complex moral models will have higher variance as they paralyze action. For example, many religious texts have complex moral guidelines, so we defer the interpretation to our denomination and priests, yielding higher model variance. On the other hand, simple moral guidelines like the Ten Commandments might incur significant contradictions, but are far more actionable.

While small and relatively trivial, this example illustrates how we can cross-apply other fields to guide understanding of ethical systems.

It’s not a secret that different fields often employ their own jargon, which makes their ideas (slightly) inaccessible to other fields, but connecting ideas across fields (e.g. bias-variance tradeoff and moral philosophy) can illuminate how the same logic often underlies different results.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: